Tales of Writing Heroism: Part the Second, Wherein We Discuss the Big Sleep

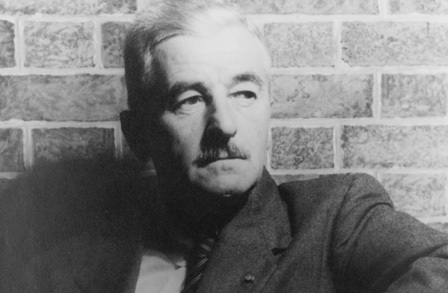

Raymond Chandler didn’t publish a novel until he was 52. Though his potboiler short fiction saw publication in many magazines, it this late career that would propel him to fame and see his book, The Big Sleep, a combination of two stories itself, made into a classic of film noir. The movie was one of many Bogart/Bacall vehicles (Bogey was about Chandlers age, Bacall, his child bride, was, of course, fresh out of high school) and boasted legendary director Howard Hawks. Adapting the screenplay were three writers, including one long-winded bourbon enthusiast named William Faulkner. The other two writers, Jules Furthman and Leigh Brackett, were presumably there to tone Faulkner down. He was infamous even then for writing unfilmable, unsayabale dialogue. Bogart would take one look at the script and turn to Hawk and say “Am I really supposed to read all this?” And so rewrites were frequent.

Like many Film Noirs, The Big Sleep had what most consider to be an incomprehensible and convoluted plot. (Harry Cohn, the head of Colombia, once offered a thousand dollars if anyone could explain to him the plot of Orson Wells’ Lady from Shanghai.) It was also heavily censored in comparison to the book, which featured so much salacious material that it’s easy to understand its popularity. The book is populated by Jewish pornographers, sociopathic heriessess, interracial couples, murderously jealous gay lovers, pitiless thugs, crippled millionaires, and femme fatales. Some adaption was needed.

Director Hawks brought Faulkner on personally, this being their second project together, and in those days writers were kept on set for quick rewrites and advice. The studio system required a breakneck pace and just coming back tomorrow was not normally an option.

Director Hawks brought Faulkner on personally, this being their second project together, and in those days writers were kept on set for quick rewrites and advice. The studio system required a breakneck pace and just coming back tomorrow was not normally an option.

The midpoint of the Big Sleep, a hard to shoot scene showing the investigation of the death of the Sternwood family chauffeur, is where our tale of Heroism takes place. The chauffeur apparently drove the Sternwood’s expensive car off a dock, and Bogart’s character, Phillip Marlowe, is unsure if the death was suicide or murder. Ever the method actor, Bogart wasn’t sure either. When he asked Hawks what his character actually thought, what his motivation would be, Hawks admitted he didn’t know if the driver had, in fact, been murdered.

Hawks admitted he had no idea. He called for Faulkner, who I imagine was seated in a folding chair with a mint julep in his hand, chatting up a script girl. After a series of incomprehensible mutters and drunken boasts, Faulkner admitted he didn’t know either.

An exasperated Hawks decided to send a, at the time, very expensive telegram to Raymond Chandler himself. Sitting down to diner, Chandler read the letter aloud to his wife. “The actors don’t know if it’s murder,” said the hack. “And the director doesn’t know, and the writers don’t know. And hell, I don’t know either!”

The best piece of advice Chandler ever gave: “If you don’t know how to continue a scene, just have someone come into the room brandishing a gun.”